Multiverse explores new ways to read and write fiction with artificial intelligence. It asks questions about Human–AI interaction by investigating the future of interactive literature. Central is the eponymous prototype, a real-world interactive literature system that acts as an evolving test bed for literary experimentation.

The project evolved from my master’s thesis in interaction design. It has found use in research workshops, teaching and as a tool for writing.

The first period of the work primarily investigated ways of reading AI–written fiction, documented in the published material and this essay. Current research explores novel interaction modalities for co-writing fiction with AI. If that sounds interesting to you, get in touch.

Multiverse and is a collaboration with Maliheh Ghajargar, Jeffrey Bardzell, Anuradha Reddy and Line Henriksen. The prototype is distributed as open source software but requires a GPT3–API key to run.

Note: Images and videos might feature banding artifacts caused by the compression’s inability to handle subtle gradient aminations. These are not visible in the actual application.

- Introduction

- Designing multiversal literature

- Reflections

- Acknowledgments

Introduction

Anthropocentrism in AI

The present moment of AI creativity is in a rather peculiar state. Generative image models, like the canonical DeepDream, are “allowed” radical exercises in form. Models like Stable Diffusion and Craiyon flood social media with a tide of fully automated mashup extravagance celebrated as a new era in creativity. However, the same playful attitude does not seem to apply to our AIs’ literary works. Texts created by large language models get judged against conservative human authorship. A picture is worth a thousand words, creatures of interpretation. A text is, at least on a surface level, very concrete, far more prone to scrutiny. AI-made images capture our imagination through strange hallucinations. Their writing stands out as drunken impersonation.

This discrepancy intrigued me. Are the writings of these models nothing but stochastic ramblings? Or, is our anthropocentric gaze blind to this thing, weird and novel? Multiverse began as an attempt to approach and appreciate AI writing as a novel medium.

Anthropocentrism refers to the notion of the human as separate from nature. Of course, such a challenge to the status quo is nothing new. The I Ching, written three thousand years ago in Chinese antiquity, uses chance as a method and motive. The modern movement was full of formal experiments like Dadaist cut-up poetry. Where the post-modernists questioned authorship through contradictory, intertextual works, personal computing is inseparable from the ambitions of hypertext. The latter is of particular interest as it manifests a non-sequential literary medium. It states our experience as the base of comparison and understanding. It follows that the “intelligence” in artificial intelligence approximates the “human.” Who or what the “human” might be is often left implicit, a function of the ruling culture. In approaching AI literature, I argue that we must let go of this anthropocentrism. To do so requires an open mind and a critical re-evaluation of what literature can be.

Literature as sequence

Conventional human literature follows a linear structure. A story has a beginning and an end. Between these comes a linear sequence of passages that unfold the narrative. This ordering is a fundamental property that affords authors control over the experience. Literary devices like suspense (withheld information) or plot development (new information) function sequentially.

Contemporary AI lacks an “understanding” of human notions of story or sequence. They struggle especially with continuity, intentionality, and disambiguation of characters. But is this a shortcoming of the model or the medium? Can we imagine a fiction free of sequence with room for something beyond the current convention?

Of course, such a challenge to the status quo is nothing new. The I Ching, written three thousand years ago in Chinese antiquity, uses chance as a method and motive. The modern movement was full of formal experiments like Dadaist cut-up poetry. Where the post-modernists questioned authorship through contradictory, intertextual works, personal computing is inseparable from the ambitions of hypertext. The latter is of particular interest as it manifests a non-sequential literary medium.

Hypertext’s distinguishing feature is the interlinking that affords arbitrary non-linear access. The granularity of this linking and sequence is up to the author. The Web has settled into a convention of linking complete, individual documents. Contrast this to hypertext fiction, which uses linking to create non-sequential narratives.

Despite the ubiquity of the Web, non-sequential hypertext literature remains exotic. Carter (2002) identifies the "expectation of order" as the leading blocker for would-be hypertext writers. Interconnected narratives converge toward exponential branching, resulting in a seemingly endless text to wire and edit. Whether cultural or a hard limitation of the human mind, hypertext seems a tough sell in a culture of sequence. However, these attributes make hypertext compelling for an AI free of cultural blockers and cognitive limits.

Despite its anthropocentric ambition, contemporary AI lacks many of hypertext’s cultural blockers. An LLM is, by and large, a function that inputs existing text and outputs something new. For example, where a human would struggle to author single branching narratives, an AI has already written five. The fragmented nature of linked pieces suits an author that struggles with long form. Instead of creating a finished work in one go, AI hypertext affords interactive, co-creative discovery. Imagine a literary medium where a simple starting point story unfolds into a branching, infinite possibility space.

Multiverse presents a literary model that combines hypertext’s AI–compatibility with limited sequentiality. This combination manifests in a tree structure through experimentation with hypertext networks. Trees are simple to manipulate programmatically and map well to the prompting models. They also introduce limited sequence, breaching from a stable root prompt. Early user testing found that this aided in comprehending foreign hypertext-like structures. Pope (2006) argues that "idiosyncratic and unfriendly" hypertext interfaces discourage readers. Having a "stable point" affords a grounding that can encourage discovery and experimentation. However, a data structure alone does not make an interface. The following section details the major design decisions in the Multiverse prototype by listening to human and AI feedback.

Designing multiversal literature

The feeling of reading

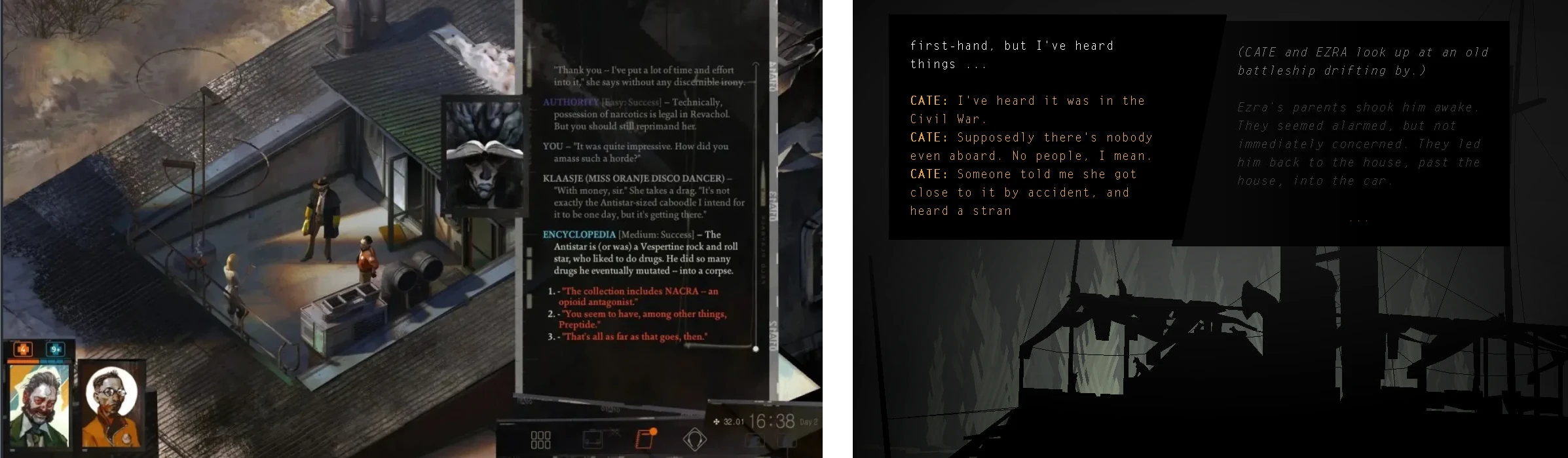

How do you feel when you read a book? This archetypical interaction design question is the main driver behind the most interesting design decisions in the project. As with any new kind of interface, first-glace often finds Multiverse as difficult and dense, more akin to something from a video game than iBooks. This is largely intentional. The broad strokes of this design have remained mostly intact from the original prototypes, initially inspired by the dialogue trees of titles like Disco Elysium or Kentucky Route Zero.

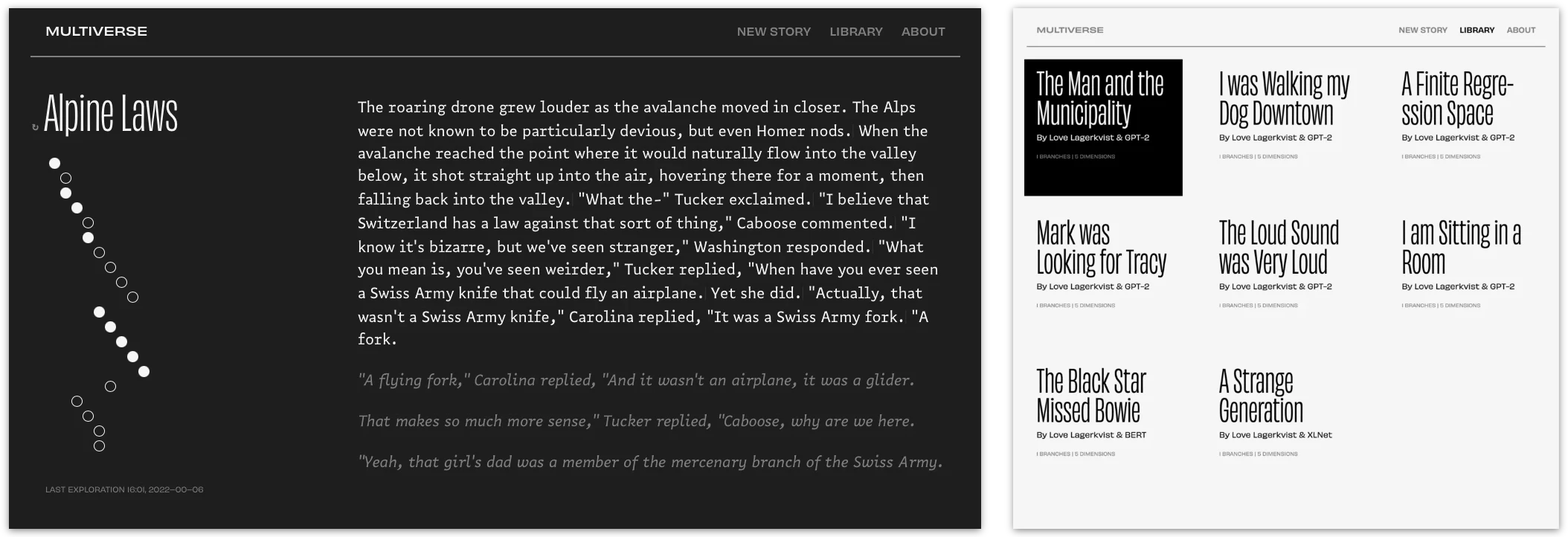

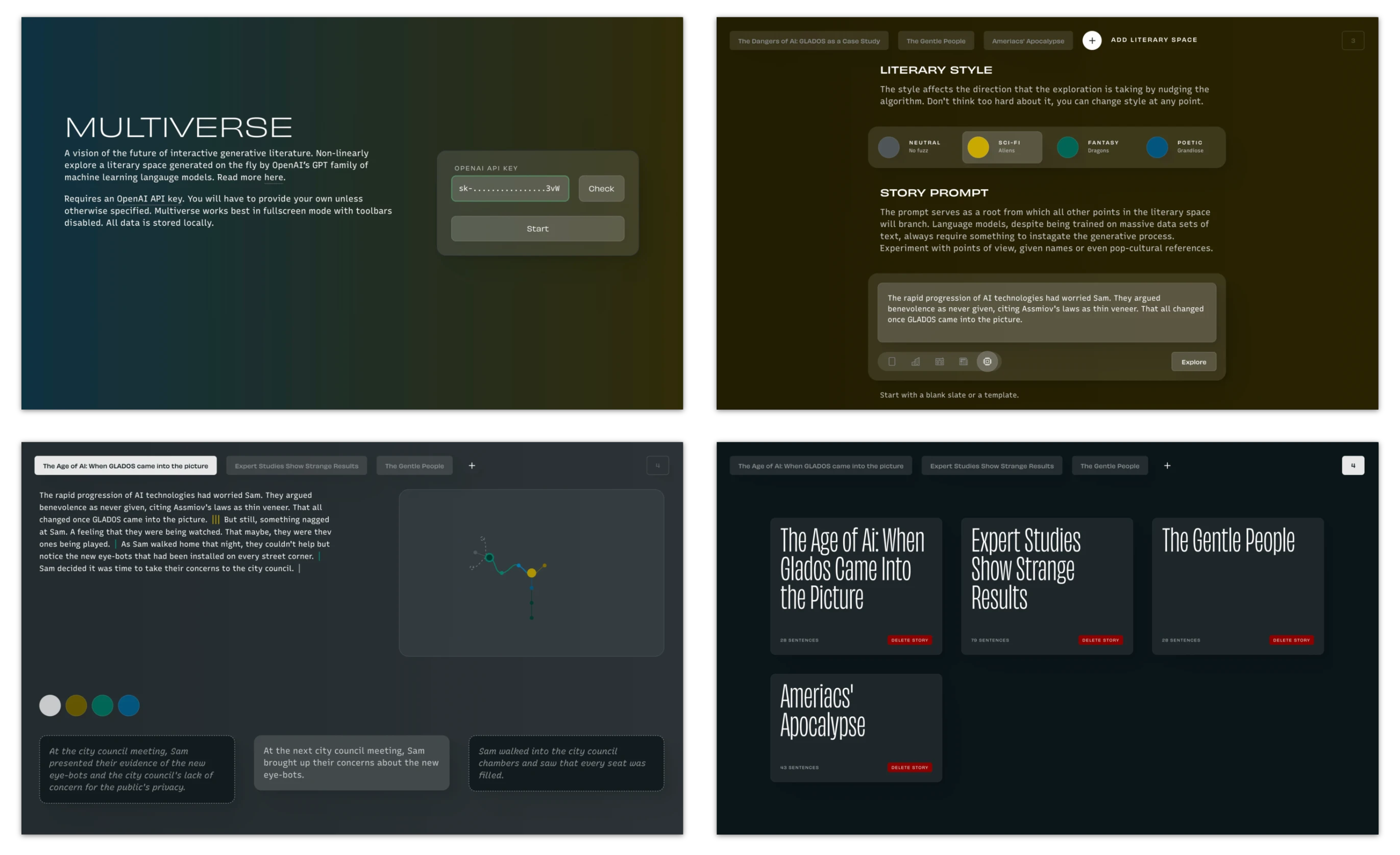

There are two major iterations of Multiverse: The initial prototype developed for the master thesis and a more refined version used in the second research paper. The original version features a flat interface referencing authoring tropes like semi-proportional fonts, extensive library features, and typewriter-inspired micro-interactions. An interactive, abstract tree diagram in the left sidebar visualizes the literary space. This version also includes the ability to hot-swap the AI model during the creation of the story, the albeit novel feature axed as the project transitioned from a self-hosted back-end to the GPT-3 API.

The initial version was an intriguing proof of concept, but the aesthetic choices felt cold and uninviting. The typewritten manuscript is exciting for a writer but not as much an artifact we connect with as readers. Reversed type on a flat background made all the stories a user writes feel similar, missing variation and any representation of the AI as an active subject. As such, one of the main UI-research questions driving the second iteration was to explore what reading-writing multiversal literature should feel like, and what role the AI plays in that.

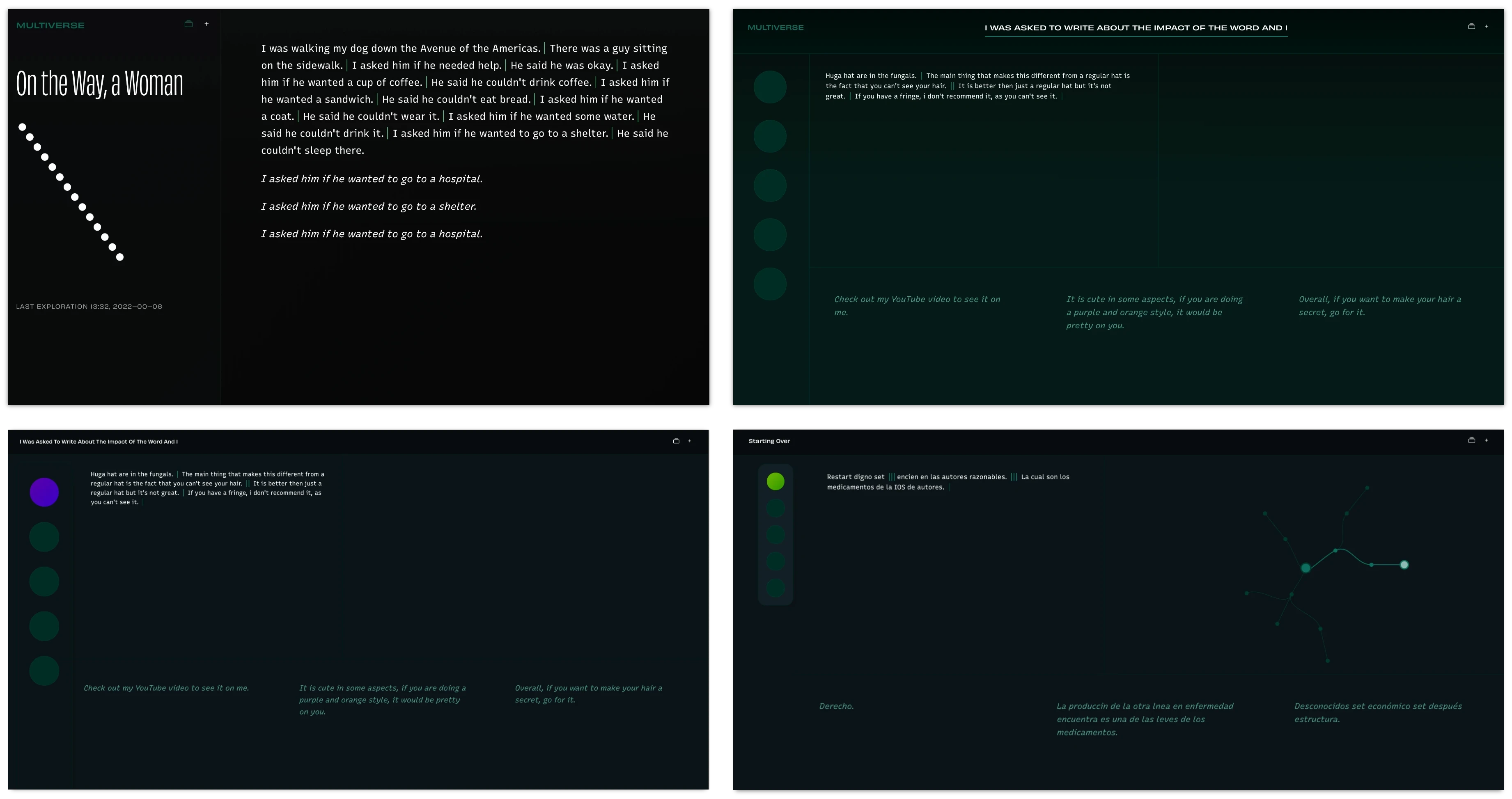

There is still a large gap between traditional print experience and e-reading, be it on a dedicated device or a general purpose screen. Automatic typesetting is rough at best, every book looks the same, and the only cue that something has progressed is a literal progress bar. The loss of print affordances also comes with a loss off vibe. Reading the paper- or hardback version of a book arguably constitutes different experiences. Most of the digital applications we interact with daily do not take such qualities into account. Multiverse tries to break free from the faulty ambitions of the crystal goblet by channeling the kind of meticulous micro-interactions Steve Swink calls “game feel.” Going deeper into a story should feel like a meaningful step into an exciting unknown. Navigating the space has to be a swift, fluid movement. The vibe should shift as we temporarily hand over agency to the AI during generation.

Prototyping with feeling in mind is noticeably different from conventional practice, requiring a delicate balance between high-enough fidelity while remaining agile. This means spending time fine-tuning affordances and animations through extensive testing. The final iteration, detailed below, skews towards a relatively techy direction that user testing found an effective, albeit cliche, way to accentuate the “AI-ness” of the application. The agency of the AI is represented not as a graphical avatar but as the application as such. The background moves with a subtle animation that accelerates when the AI is “in control,” generating new sentences. The human user can influence the AI’s direction by changing between a set of pre-trained literary “styles,” each represented by a color change throughout the application.

The resulting is a responsive single-screen interface that deals with information density through rich interactivity.

Single-screen interfaces

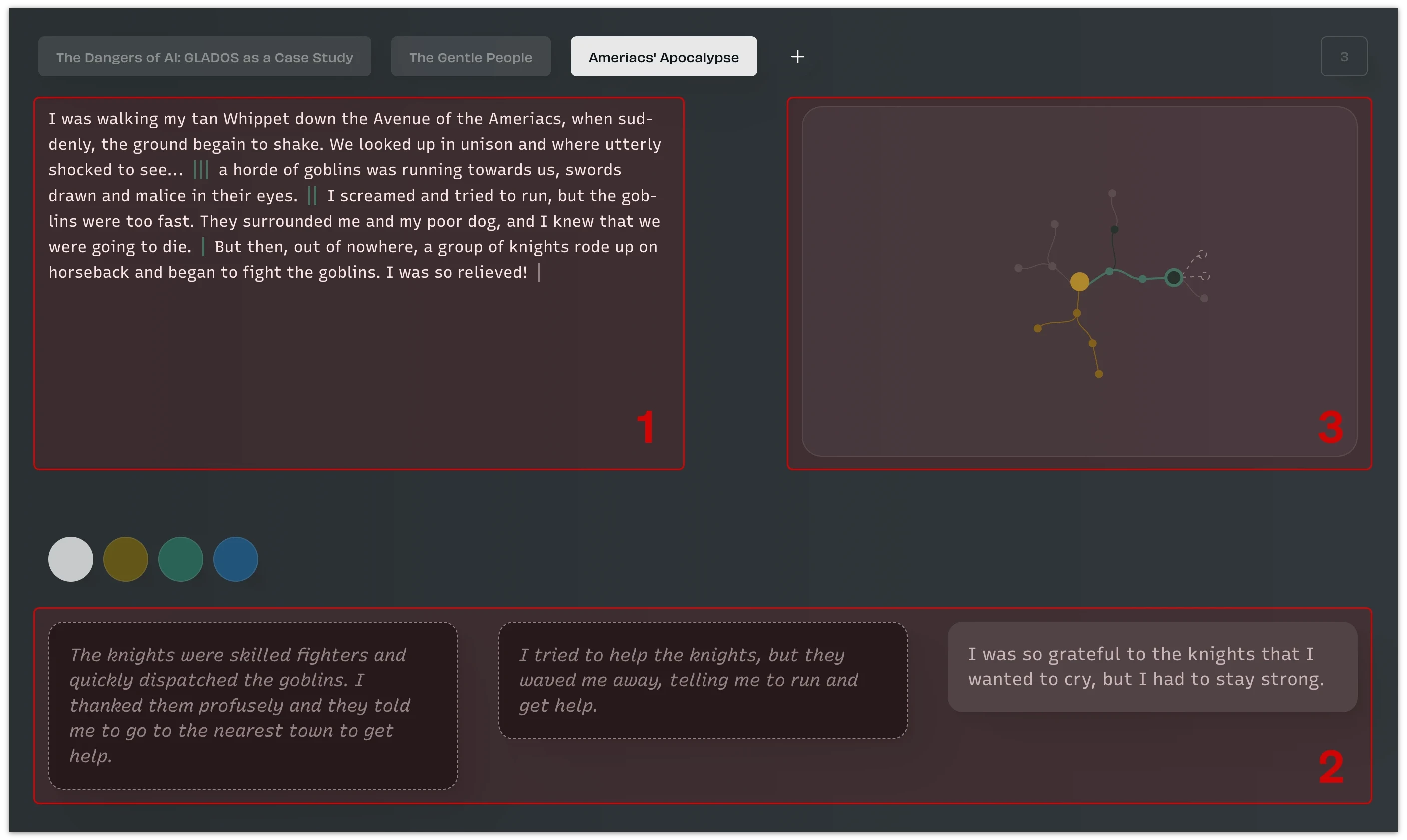

A user of Multiverse spend most of their time staring at letters in the story view, the place for reading and co-creating with the AI. At its core, the program follows a strict design philosophy where the action takes place in a modeless, single-screen interface. It features three main sections: The current story ➊, possible continuations ➋, and the map ➌.

Displaying the state of a system with multiple tightly coupled views is not necessarily all too novel. Information designer eremites Edward Tufte (1997) discusses the value of complementary representations for understanding both large and small multiples of data. Matthew Davies (2019) of Subset Games employs highly fluid "single screen interfaces" that serve two purposes: They afford the player agency in complex real-time situations and give the designers a consequential limitation. Anything you add must fit into the already dense single screen through integration or addition to the existing elements. Most desktop "document-based" applications constitute a kind of single-screen interface. However, they tend to grow inward, hiding auxiliary information in modal views. Multiverse forgoes the pedagogical ambitions of progressive disclosure through a clear interaction hierarchy. Each section has a clear direction:

Davis, Matthew (2019). Into the Breach Design Postmortem , Game Developers Conference.

Selecting a continuation in ➋ progresses the story, moving in a downward direction of the current path.

Selecting a previously visited sentence ➊ performs the reverse, moving the reader up the path.

Exploratory or comparative movements go via the map ➌, providing direct access to any part of the tree.

These movements come together to form an interface that has proven intuitive despite a high information density and the previously discussed issues inherent in the hypertext format. The responsive coupling between the three views of the literary space affords an exploration experience. Whether or not it feels right is a purely subjective experience, but I find it a joy to co-create with.

We have done extensive research using the prototype, both auto-ethnographical and with external users. This is dicussude in great detail in the two published papers; the curious reader can find more information there. Instead, I will share some more personal and speculative reflections on the process of making tools using AI. These are the thoughts one desperately tries to weave into an academic paper better suited for a free-form essay like this one.

Reflections

Human-AI interfaces to come

Three years of on-and-off work on Multiverse has made it clear that many Human-AI interfaces are left to make. One might argue that this is an obvious statement. The development made to LLMs during the slow process of writing this eassy in fall of 2022 alone warrant many more chapters. However, like many obvious things, this realization possesses surprising depth. We suddenly find ourselves in a situation that requires interfaces for applied ethics and a co-existence that reaches beyond the screen.

Linus Lee (2022) has begun charting a course towards AI interfaces that go beyond remixes of the prompt, a space Multiverse arguably occupies. The evolutionary path of Human-Computer interfaces from textual to graphical representation is evident in hindsight, channeling a rich history of human knowledge expression. However, simply reenacting this process with AI is sure to fail. Prompt-based interfaces are a powerful modality, yet, they operate on a level of uncertainty prohibiting deep understanding and mastery. Currently-existing AI is by all accounts a weak approximation of AGI, yet it is already at such complexity that its inner work resists comprehensible representation.

Unable to visualize AI, we must invent new interfaces and languages. For example, we use different lingual modalities when interacting with animals and other non-human entities, communication where both parties have adapted to a different baseline of understanding. The work done with Multiverse is far from anything that approximates this goal. However, the research indicates the potential of tightly coupled, interlinked, and multimodal interactions in building intuition for complex uncertainties. The elaboration of these principles is one of the main aspects that guide the project’s next phase.

Writing fiction with AI

The focus on reading AI-written fiction was an essential first step in finding ways to co-create with non-human beings. At its core, to read is to take something seriously, to validate its value as a creation worth our attention. However, there is a clear limit where current models struggle to produce narratives of greater length and substance, even with multiversal methods. As such, the next phase of this project aims to investigate new ways of writing fiction with AI and humans as active co-authors.

The goal is not to create a “Grammarly for fiction.” Instead, the basic principles behind the first phase of Multiverse still stand, a non-anthropocentric approach to AI to imagine novel mediums and their interfaces. The composition of different prompting modalities forms a Turing complete design space. Summarization, description, and completion appear as primitives from which we will build new writing methods.

Let us imagine that we are writing a short science fiction story. The first few pages flow easily, after which the text seems to develop some intangible friction. However, diagnosing the cause of such a rut can be difficult. Is the message incoherent, are the scenes getting too cluttered, or is it just not possible to find a way forward? It is easy to see how one could configure an LLM like GPT-3 to provide “interpretations” of passages using summarization and description, suggesting alterations that better fit a stated vibe. Such prototypes are already in the wild, but they often focus on single features. A key enabler will be when we can run these processes simultaneously, with multiple interpretations. Therefore, the model should not be a small, pop-up part of the interface; it should be the interface. The current differentiation between prompt and output is arguably a technical dependency. One of the goals of the next phase of this research is to find ways to blur this line, affording a much-needed integration with a non-anthropocentric voice.

Allowing for the artificial

The first iteration of Multiverse used OpenAIs GPT-2, the predecessor to GPT-3. The previous model is, by most accounts, inferior. It is less proficient art zero- and few-shot learning and much less coherent. Where GPT-3 has a decent grasp on recurring motives, its predecessor confuses pronouns, names, and places. Yet, these “deficiencies” also made it a lot more interesting to read and write with. GPT-3 is polished but predictable. When it fails, it does so in rather dull ways. Instead, it imitates a human by reminding you that most things we write are uninteresting. While this simulated domesticity is a feature of GPT-3 as a production model, you would not want a chatbot to transform into a rouge slam poet; it limits its ability to do creative writing.

One way to solve the issue of limited creative prowess is by making more advanced and appropriate language models. For example, the inspirational work of researchers like Mirowski et al. (2022) clearly shows that there is much to gain from this approach. However, a technological trajectory still sidesteps questions of how we relate and interface with our AI companions. For example, our research found that the activity of reading with Multiverse often turned into a task of “caring for the AI,” making creative decisions based on an intuitive likelihood of garnering the most coherent generations.

Caring for a dull reflection of ourselves raises a question: What could we create if we abandoned the conceit of AI as an imitation of the human mind? If our AI models on echoes of ourselves, can it create something novel? How would a feral GPT-3 scale model communicate its strange conception of the world? Would intelligence made from numbers not have to be a different being all of its own? How would a feral GPT-3 scale model communicate its strange conception of the world? Would intelligence made from numbers not have to be a different being all of its own?

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my collaborators Maliheh Ghajargar, Jeffrey Bardzell, Anuradha Reddy, and Line Henriksen, my thesis advisor Anne-Marie Hansen, and Benjamin Maus for all of his UI feedback.

References

- Carter, L. (2002). Argument in hypertext: Writing strategies and the problem of order in a nonsequential world. Computers and Composition, 20(1), 3-22.

- Pope, J. (2006). A future for hypertext fiction. Convergence, 12(4), 447-465.

- Swink, Steve (2008). Game feel: a game designer’s guide to virtual sensation. CRC press.

- Tufte, Edward (1997). Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative, Graphic Press.

Davis, Matthew (2019). Into the Breach Design Postmortem , Game Developers Conference. - Lee, Linus. Supposing better interfaces to language models (2022).

- Mirowski, P., Mathewson, K. W., Pittman, J., & Evans, R. (2022). Co-Writing Screenplays and Theatre Scripts with Language Models: An Evaluation by Industry Professionals. arXiv.